Looms, Threads, Geographies

Connecting Cultures. Maria Lai, the loom, the geography of imperfect threads.

Eugenia Paulicelli, Queens College e Graduate Center, The City University of New York

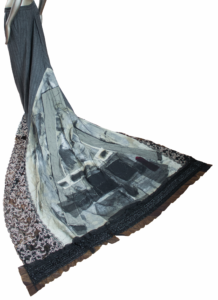

“Mondo in fuga” evoca un viaggio astrale di cui non si conosce l’inizio nè la fine. “Copiavo Leonardo Da Vinci, di cui vidi a Firenze le mappe inventate” ricorda Maria Lai

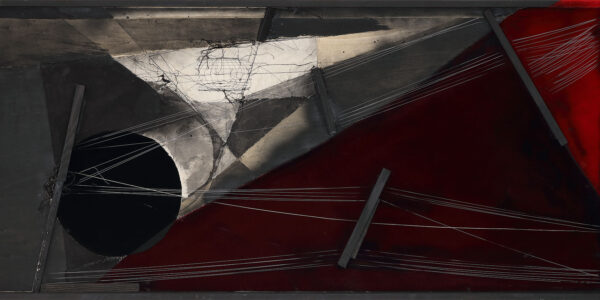

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio c. 1971-1975. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

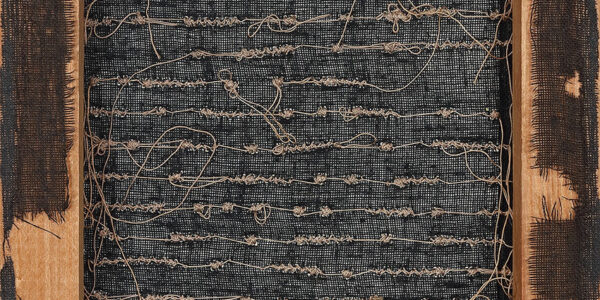

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio c. 1971-1975. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Autobiografia, 1980. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Autobiografia, 1980. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Senza titolo (Telaio), 1972. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

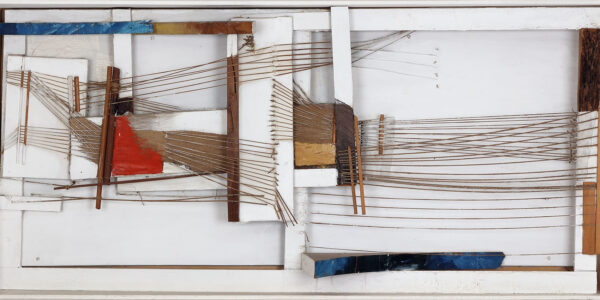

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Senza titolo (Telaio), 1972. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio in sole e mare, 1971. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

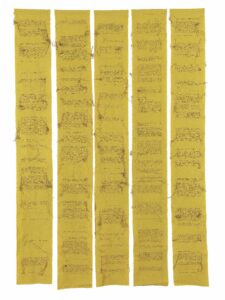

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio in sole e mare, 1971. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio, 2010. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

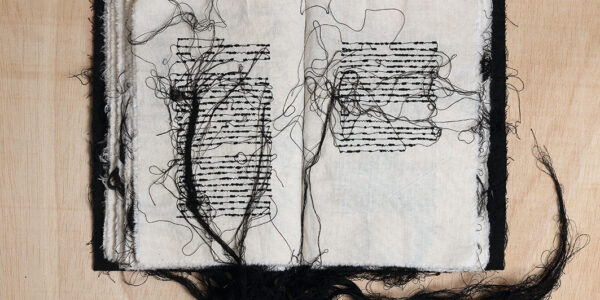

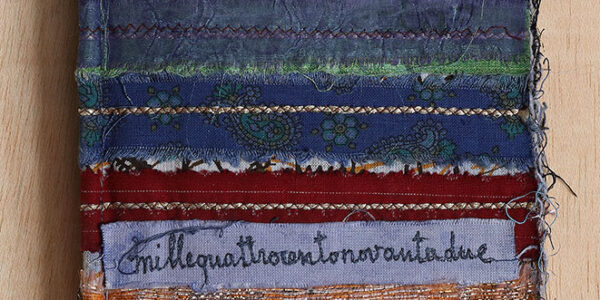

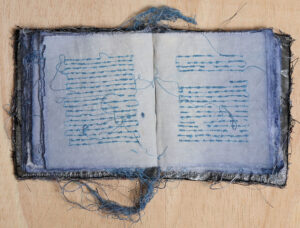

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Telaio, 2010. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Voce di infinite letture, 1992. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Voce di infinite letture, 1992. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Fili di vela spaziale, 2007. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

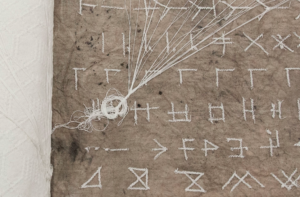

Lai, Maria (1919-2013), Fili di vela spaziale, 2007. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013),La costellazione di Raffaello, 1983. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

Lai, Maria (1919-2013),La costellazione di Raffaello, 1983. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013),Progetto per ordito 64/06. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

Lai, Maria (1919-2013),Progetto per ordito 64/06. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu. Lai, Maria (1919-2013),Millequattrocentonovantadue, 1992. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

Lai, Maria (1919-2013),Millequattrocentonovantadue, 1992. Photographer: Marco Anelli. Image courtesy of Olnick Spanu.

In the fall of 2019, I organized a workshop for Italian teachers that focused on integrating content in the teaching of a foreign language, Italian in my case. As you may know already, I am a professor of Italian at Queens College where I direct graduate studies. My teaching runs parallel to my research on fashion. Over the years, I have been interested in exploring how to integrate the study of fashion and culture in the learning a foreign language while also working on the idea that fashion can be studied in a broader framework connected to larger disciplinary domains. I have experimented with the creation of connections that bridge the research behind The Fabric of Cultures project, Italian Studies and the study of Italian as a second language.

Last fall, the workshop I organized focused on Leonardo Da Vinci to mark the 500th anniversary of his death. Our contribution to the celebrations was devoted to a lesser known field of his work, namely his textile design, his reflections on draping according to the different consistencies of the fabric on the body, the changes in women’s and men’s fashion, on hair, and his projects for textile looms and machines. My aim was to show how for Leonardo thinking about clothing (Scientia habitus) fabrics, textile techniques and production connected the different domains of knowledge, art and science, aesthetics and culture, all attesting to the multifaceted dimension of Leonardo as both a scientist and an artist. Through his work and his written reflections, we can better understand the culture of Renaissance Italy.

This is a time in which fashion and clothing gained currency through their double feature as a manufacturing industry and as powerful symbolic force, as testified in the literature of the period. The writer and diplomat, Baldassarre Castiglione,for example, theorized the art of sprezzatura (art of concealing art), which he extended to the many manifestations of culture, including the art of dressing. It is interesting to note that some of these techniques of the art and the discipline of style and of the control of appearances are also common in Leonardo’s writings. Leonardo, in fact, met Castiglione while he was living at the Sforza court in Milan. Last year, several exhibitions in Italy were dedicated to Leonardo. One in particular, held in the Textile Museum near Florence, was dedicated to the art of textile in the Textile Museum in Prato near Florence, Leonardo Da Vinci, Ingenuity and Textiles.

A thread connects Leonardo Da Vinci to Maria Lai. Last September while I was preparing the workshop, I took a research trip I took to Italy where I visited and was struck by an exhibition on Maria Lai’s work entitled “Holding the sun by the hand” at the MAXXI Museum in Rome. On my return, I decided to change some of the content and structure of the Italian class I was teaching and introduce my students to the work of Maria Lai.

Learn more about Project/Italian 204

This project is a further development of The Fabric of Cultures. By the way, the thread connecting Leonardo and Maria Lai was not my invention or something merely related to my private life. It was that too, of course, but it was far from the only one; another exhibition, which I was not able to visit, held last fall at Villa Carlotta (near Como), also connected Leonardo and Maria Lai. It was entitled “Telai e trame d’autore. Da Leonardo a Maria Lai” (Artists, Looms and Weaves. From Leonardo to Maria Lai) and was a homage to the great textile tradition of the Como area. Here on show were contemporary art works paired with textile machines executed on the models of Leonardo’s drawings. In addition, Maria Lai herself has affirmed that for her own “Geografie” (Geographies, in the late 1970s) she was inspired by the imaginary maps drawn by Leonardo.

My first discovery of Maria Lai’s work came while I was preparing an earlier exhibition The Fabric of Cultures. Fashion, Identity, Globalization (The Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College, 2005-2006). Maria had collaborated with one of the designers we featured in the show, Antonio Marras (Alghero, 1961), also from Sardinia. I was intrigued enough to explore in greater detail Marras’ relationship with the historical past, tradition, the south (where I am from), identity, multi-locality, and globalization. Marras is an important figure for me. His work was again an inspiration in the curatorial process of the 2017 Fabric of Cultures. Systems in the Making exhibition.

In 2006, I collaborated with colleagues at Queens College, Prof. Elizabeth Lowe, expert in fashion and textile and Dr. Amy Winter, then director of the Godwin Ternbach Museum where the exhibition of that year was held. Our initial purpose was to build bridges on campus and at CUNY in general (at the time I was co-teaching an experimental course focused on fashion entitled the Fabric of Cultures as well as an undergraduate course at Queens College) and to highlight how fashion and textile deserve academic attention in a university context. In addition, I found out that Queens College housed two very important collections, one of costumes and one of art, textile, paintings, and other objects etc. (The Queens College Fashion and Textile Collection). The process was not easy and demanded a considerable amount of work, but the result was fantastic and I am still very proud of that collaboration. We produced a catalogue edited by Amy Winter edited, which preceded the Routledge anthology I co-edited with Hazel Clark from Parsons, The New School of Design. In the process of conducting research for the exhibition, I identified designers such as Marras, still relevant today for our discussion on post-modernism and arte povera. In fact, the essay written by Elizabeth Lowe in the 2006 catalogue she uses Marras’ (Evening Jacket and skirt) to illustrate fashion and postmodernism and its implications with tradition and avantgarde art, such as in this case of “arte povera.” She says:

In addition to borrowing ideas from various traditional sources, postmodern designers sometimes combine elements in a single outfit that defy time-honored notions of aesthetics and good taste.

The ensemble by the Italian designer Antonio Marras seen in the section on ‘The Poetry of Dress’ (pp.42-45) in the catalogue is an excellent example. The base of the jacket is a man’s wool suit jacket—one once owned by his Sardinian uncle, as a matter of fact—employed to make a personal and political statement about memory, history, identity, class and the folk tradition of recycling and refashioning materials. At the neck however, ostrich feathers have been added and sequins are hand sewn inside the hip pf the jacket….. Clearly these choices call into question customary standards of gender and identity…” (Lowe: 19)

The jacket is a border crossing and a collage of signs belonging to different discourses and registers. But I found the skirt that goes with the jacket the most interesting piece. This would become an inspiration and provide the concept for the 2017 exhibit.

The skirt is “a study in ambiguities” and contrasts. (I would emphasize contrasts rather than contradictions). The skirt is made by unstitching the trousers (I remember in the 1980s that this was a way to reuse and refashion jeans by making a skirt out of them…but using men’s pants from a suit to make women’s skirts).

The back of Marras’ skirt has a very long train made out of a painter’s drop cloth, splashed with painted brushstrokes, stitches and visible threads and refinished at the border with some overlay of netting, decorated with beading, wool patches, visible basting threads that also cover the train as a superimposition of the base cloth. In this garment, the ephemeral and the impractical are in dialogue with the utilitarian and the durable. Here apparently contrasting domains and materialities are interrogated in the skirt and its different components in terms of fabrics and processes of decoration. The skirt captures the gesture of the maker and its process. The train is treated as a canvas while at the same time the past (the old suit of an uncle) is used and refashioned into the present not as a merely and/or superficial collage of quotations. Rather, they expose the seams of the past on the surface of cloth and into the present…. layering of material, fabric, paint and decorations that create the “surface” of the skirt.

This is a surface that has a depth and is significant in its layering. At the beginning of her study, Surface, which deals with materiality in the virtual age, Giuliana Bruno refers to a quotation by Lucretius in Rerum Natura, stating that the “image is a thing,” insofar as it is configured as a cloth, or that the material of an image manifests itself in its surface (Bruno: 2014, 2). As an image and as an object, Marras’ skirt addresses similar concerns.

Needless to say, the Marras skirt was the center piece of the curatorial process that the new team put together for the 2017 exhibition at the Art Center at Queens College.

This skirt also shows the convergence of the language of “arte povera” and the multimedia work of Maria Lai. See, for instance, the similarity in textural consistency and discourse between the detail of Marras’ skirt and Maria Lai’s work on fabric.

A FIL ROUGE

A fil rouge has run through the project for several years. Red was the thread present in Marras’ collection of 1991 (to which the skirt belongs) and in the books accompanying his research and encounter with artists such as Maria Lai. The 2017 exhibition revisited his work and validated other parallel journeys in the fields of fashion, textile, the debate on innovation in sustainability and ethical practices.

On April 27, 2017 Marras’s Milan concept store and art space “Nonostante Marras” hosted an exhibition and events around Fashion Revolution, a movement started in the UK following the tragedy of Rana Plaza where on April 24th 2013, more than a thousand garment factory workers died.

In the 2006 exhibition and project, identity was framed as a fluid process of becoming. Marras’work embodied this concept.

In the catalogue of The Fabric of Cultures exhibition in 2006, Antonio Marras wrote a foreword, here are some excerpts:

Border can be a limit, as well as opportunity

A line that cuts and divides, but also the place where things meet. A separation, but also a rule with which to come to grips, to know, interpret, understand, absorb. The border is a state of mind, the extreme point of thought that always poses a challenge: respect it or cross it? Admit impossibility or transform it in the deep regions of change?

[…] Time, gender, use are also borders to be crossed time and time again, digressing from everyday objects to give them a new life, another chance to honor the memory of those who have lived before us, through their personal things. A creative process where nothing is destroyed and everything is re-created, takes on new forms and the new beauty in detournement that reflects the fluid character of the contemporary that transforms objects, making them live and live again, emblems both of those who made them and those who use them.

My first collection was made of redesigned garments that came from the wardrobe of my uncle who moved to America. […] Imperfection means a lack and lack suggests expectation. The edge without a hem awaits a hand to finish it. Imperfection doesn’t let you forget it: it’s a slap in the face of our mentality, it triggers cognitive dissonance.

If there were no cognitive dissonance, if everything were to happen according to predictable rules, if that hem had been finished and we could finally forget about it, then there would be no reason to continue thinking. […] We tend to find imperfection intolerable, and this is precisely its strength: in the attempt to justify it, to close it, to bring it back into the realm of the well-made, we are forced to invent new solutions. The new never comes from perfection. The new comes from holes, cuts, and emptiness, from a lack that prevents the mind from finding rest.

Antonio Marras, (The Fabric of Cultures, 2006)

I worked on integrating the work of Maria Lai into my Italian class by means of a project that was executed in different steps, working both inside and outside the classroom. I was happy to see that the 10 students in the class, all from different backgrounds, responded well to the idea and the activities in which they were engaged. Although the course was not required, it functioned as a bridge that connected students to more advanced courses where students would have the opportunity to express more complex ideas in the language.

The title of the project was: “ Scrivere, tessere, comporre: Tenendo per mano la lingua e la cultura” (Writing, weaving, composing: holding language and culture by hand)

We chose the theme of the thread, as this is a central core in Maria Lai’s art. Sewing, weaving, writing are acts in which the literal and the symbolic interact. In her work, there is a strong component of tactilism, which we addressed as we studied fashion, clothing and materiality. In Lai, the image has an haptic and tactile dimension. Similarly, the words she composes with needle and thread on fabric or on the clothing that she has made for some women family members, have a tactile consistency. Lai says: “Touching the fabrics would be important, however even looking at them is like touching them, because there are tactilities in the gaze.” This is the materiality that words possess in poetic language. This tactile dimension is both an ontology (being) and epistemology (knowing) present in the arts, especially visual poetry (“Materializzazione del Linguaggio”, Bentivoglio, Venice Biennale 1978), film and screen media and of course in fashion and clothing. (See here the work of Giuliana Bruno, Surface. Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media, Antonia Lant; Laura Marks, The Skin of the Film, etc.)

The topic of thread, which is so central in Maria Lai and her “Looms” (Telai), is at the heart of Sardinian popular art and in particular of that of women and their traditions. Thread in Lai comes back in her “Geografie” and maps of the world. (see Pontiggia, p16). Lai donated some of her drawings to a women run coop based in Ulassai called “Su Marmuri” that produces different kind of textiles, rugs, tablecloths etc. and has been active for 30 years.

My aim is and has been to connect teaching and research and so put together in a relational mode different paths and domains in such a way that we can interrogate practices of making and thinking that involve different tools–the pen, the needle, the computer, etc., opening up the possibility of using key words to interact with each other and so lead towards unexplored territories. In fashion, as in art and literature, we can work on single words as they are connotated by a material stratum (sostanza materica). I am thinking of words and practices such as weaving, sewing, repairing, mending, caring that with their rhythms and spaces are profoundly linked to making (homo laborans) and thinking (homo sapiens).

The critic Antonella Anedda has said that,

the needle is not a pin, the pin is transitory, stings, but does not unite, the needle gives life back to fabric, it transforms the inertia of matter in something that has something to do and see with life, skin and food.”

A long thread in the history of women connects the needle and the pen. Women writers since the Middle Ages have worked with both. Maria Lai’s work weaves fabric crossing different domains and materials: the fabric, the page, the loom etc. This gesture expresses the will and political project of occupying a space and gaining a voice and subjectivity. Her treatment of words reminds me of how imbricated language is with objects, clothing and fashion and with the notion of a rhythmic temporality. Here I would like to recall the words of art critic Pontiggia who stresses that Maria Lai’s work would be incomprehensible without her “ability to perceive the rhythms, and add the artist’s own words when she says: “Without breath the work of art is inert […]. I read only the rhythms, I did not understand them first but then I transformed these rhythms into images.” And making a further connection to Barthes’ The Fashion System, we note how he hints at the materiality of language in liberating the object from its inertia:

Everything in language is a sign, nothing is inert; everything in meaning receives it. In the vestimentary code, inertia is the original state […] a skirt exists without signifying, prior to signifying; the meaning is at once dazzling and evanescent: [fashion writing] seizes upon insignificant objects, and […] strikes them with meaning, gives them the life of a sign; it can also take this life back from them, so that the meaning is like a grace that has descended upon the object.

(The Fashion System: 64-65)

Language expresses the “surface tension” (Bruno: 2014) embodied in a garment or object so as to speak to us and thus escape from inertia.

My hope is that in this presentation I have been able to convey the connecting threads of our seminar while at the same time suggesting possible future paths.

In Italian

Esiste un lungo filo nella storia delle donne che lega l’ago alla penna, molte scrittrici hanno fatto entrambe le cose sin dai tempi del Rinasimento. Quindi in tal senso il lavoro di Maria Lai vuole anche tessere la trama di questi spazi intercomunicanti, la stoffa e la pagina, il Quadro e il libro. E dunque in questo gesto di occupare spazio, significa costruire spazio e visibilità per soggetti che altrimenti non lo avrebbero, come è stato per le donne. Ricordiamo il titolo di un’opera famosa di Virginia Woolf A room of one’s own. Quindi scrivere vuol dire costruire uno spazio per se che poi si condivide con altri.

Learn more about Project Italian/204

_______________

The Way It Is

There’s a thread you follow. It goes among

things that change. But it doesn’t change.

People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread.

But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you can’t get lost.

Tragedies happen; people get hurt

or die; and you suffer and get old.

Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding.

You don’t ever let go of the thread.

By William Stafford, 1998

_______________

The Thread

Something is very gently,

invisibly, silently,

pulling at me-a thread

or net of threads

finer than cobweb and as

elastic. I haven’t tried

the strength of it.

No barbed hook

pierced and tore me. Was it

not long ago this thread

began to draw me? Or

way back? Was I

born with its knot about my

neck, a bridle? Not fear

but a stirring

of wonder makes me

catch my breath when I feel

the tug of it when I thought

it had loosened itself and gone

By Denise Levertov

References

Altea, Giuliana, ed. Maria Lai and Antonio Marras. Lenclos de Aigua, Cagliari 2003, Project and book for the exhibition in Alghero, Sardinia in 2003.

Barthes, Roland. The fashion system. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of aesthetics, materiality, and media. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Paulicelli, Eugenia, and Hazel Clark, eds. The fabric of cultures: Fashion, identity, and globalization. Routledge, 2009.

Pontiggia, Elena. Maria Lai. Arte e Relazione, Nuoro: Ilisso Edizioni: 2017

Pontiggia, Elena, ed. Maria Lai. Il filo e l’infinito, Florence: Sillabe, 2018

SEE ALSO:

Poetic Textiles Tell a History Woven by Women

Video Lai

MAXXI:

Trama Doppia :

Loro Piana unveils textile sculptures by artist Sheila Hicks (LVMH)

15 Stylish Movies With Costumes Made by Famous Designers(Vogue)

I wish to thank Giorgio Spanu and Nancy Olnick, Magazzino Italian Art, for their kind support and for giving permission to publish Maria Lai’s work on the Fabric of Cultures site.